Prof. Chris Muller, Dozent an der Boston University, ist einer der renommiertesten Wissenschaftler und Branchenkenner der Restaurant-Welt. Auch der deutschen Gastronomie ist er durch Auftritte beim Internationalen Foodservice Forum und Artikel in Fachzeitschriften gut bekannt. Anlässlich der Corona-Krise und ihren verheerenden Auswirkungen auf das Geschäft der Foodservice-Branche, hat er für den amerikanischen Markt eine Analyse der Lage und der Zukunftsperspektiven verfasst, die wir hier freundlicherweise veröffentlichen dürfen. Denn auch für deutsche Unternehmen bietet sie viel Lernstoff.

Restaurant Organizations and the Power of the New Economy: A Pandemic, Labor Value and Lessons From the Past

By Dr. Christopher Muller

What happens to the restaurant industry when the Pandemic ends, which history tells us, it will?

The New Reality

In the worst-case scenario, tens of thousands of newly opened foodie comets, or aging and struggling veterans, or flashy places with aspirational rent that was just a bit too high, or those busy local places just staying afloat day by day, will have closed. They will be gone forever from our daily routines. Along with them will be the disrupted lives of chefs, and servers, dishwashers, and owners changed by unpayable debts and disappearing cash flows.

But on the other hand, probably for the first time ever, today the world has actually been put on notice that restaurants and bars, pizzerias and coffee shops, or wine bars and food halls are not to be just taken for granted, or merely viewed as the wallpaper on a walk through a neighborhood. These places actually matter in the global economy of the 21st Century, as do the millions of people who work in them every day.

On the front page of the New York Times on March 17, 2020 writer Neil Irwin wrote: “One person’s spending is another person’s income. That, in a single sentence, is what the $87 trillion global economy is.” What makes this argument much more powerful is he also points out that together the U.S. restaurant and lodging industries contributed $1.02 billion to that global economy. Projections are that prior to COVID-19 the U.S. Gross National Product for 2020 would have been over $20 trillion. That means the U.S. Hospitality industry should have amounted to about 5% of that annual number.

Small businesses must be the primary targets of any stimulus package

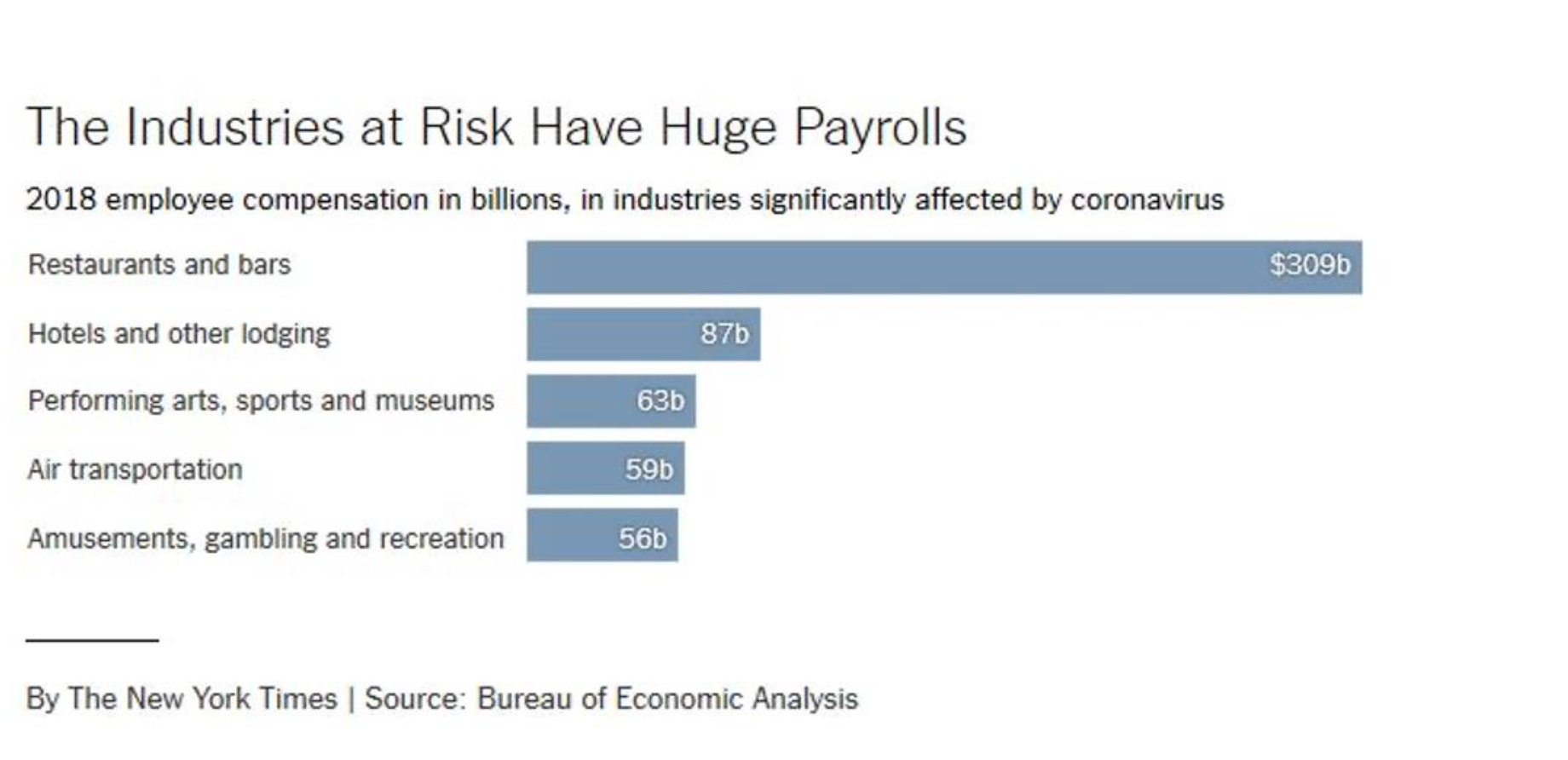

Irwin’s article also includes the graphic attached showing the 2018 payroll impact of certain key industries, with restaurants and bars leading by more than three times the linked hotels and lodging industry. Together restaurants and lodging account for almost $400 billion in income for direct workers. By comparison, on Tuesday, March 17 the White House proposed to spend up to $850 billion to counter the economic effects of coronavirus. Along with immediate payments to hourly service workers, included in the proposed options are paid sick leave, child care allowances, expanded unemployment payments, low-interest loans to small businesses, and lowered student loan costs.

These are far different than the incentives used in the 2008/2009 economic bailouts, which focused on large banks and industrial sectors such as automobile manufacturers. This time there is a public acknowledgment that the workforce and the many small businesses that employ them must be the primary targets of any stimulus package. Of these targets, restaurants, bars, and hotels are the ones most often mentioned as the highest priorities, with their travel/tourism partner the airline industry included in the mix.

Christopher C. Muller is Professor of the Practice of Hospitality Administration and former Dean of the School of Hospitality Administration at Boston University. Each year, he moderates the European Food Service Summit, a major conference for restaurant and supply executives. He holds a bachelor’s degree in political science from Hobart College and two graduate degrees from Cornell University, including a Ph.D. in hospitality administration. Email: cmuller@bu.edu

Lessons From the Past

So, what might the best-case scenario be for restaurants and restaurant employees? For this, I think we need to look back at what was happening about 100 years ago, both globally and here in the United States. Much has recently been written comparing the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic and the 1918-19 Spanish Flu Pandemic. It takes very little historical sense or imagination to project that when this current infection runs its course the world will be markedly different, and many institutions will have been altered.

But between 1910 and 1932, like today, there were other enormous changes affecting the global economy. This was a time of major social upheaval, especially in respect to the “Second Industrial Revolution” that was driving a mass movement from a rural agrarian model to an urban manufacturing one. This was evidenced by: the explosion of mass production methods (and the disruptive introduction of electricity, telephone, radio, and flight); the enormous accumulation of wealth by a few individuals and corporations resulting in unprecedented economic inequality (including “barons” Morgan, Carnegie, Rockefeller, and Ford); and the disruption of

traditional social systems (World War, labor unions, women’s suffrage, Prohibition, political revolutions, and ultimately the Great Depression).

The Second Information Revolution

Over the past two decades, similar upheaval and change has occurred as we face the “Second Information Revolution.” For the first time in history, more people live in cities than in rural areas, brought about by the search for more connected lives. Simultaneously, since 2007 we have absorbed the rapid acceptance of “smartphone” technology with instant communications, social media exposure and loss of privacy. Income inequality has wildly surpassed that of the early 1900’s (including “billionaires” Bezos, Gates, Buffet, and Bloomberg). All while large portions of society struggle to assimilate into a disruption called globalization.

But of these, the change which might resonate the most for today’s restaurant world is that for the first time in history, at the beginning of the 20th Century the value of labor was slowly being acknowledged. Without being too simplistic, mill workers, factory workers, miners, teamsters, and civil servants all saw their economic and political power, and subsequently, their wages, rise. No friend of labor, Henry Ford was forced to acknowledge: “The real power of our company dates from 1914, when we raised the minimum wage from somewhat more than two dollars to a flat five dollars a day, for then we increased the buying power of other people, and so on and on.” It can be argued that is one point in time where the nascent “middle class” of hourly workers emerges. Today we might call it the search for a livable wage.

One person’s spending is another person’s income

Keep Ford’s words in mind and go back to read the line from Irwin, “…One person’s spending is another person’s income…”. His conclusion that the global economy is poised on a precipice, one formed by the changing impact of the service industries, is very similar to the one faced by industrialist Ford in 1914. The current economy cannot come out of a possible recession if it is not built on the consumption power of hourly service work. In particular, it must be built on what Irwin calls “this perpetual motion machine” of those who work in restaurants, lodging, performing arts, air transportation, and amusements.

The current crisis, similar to the last great Pandemic, may be seen as the catalyst for the growth of a “new middle class.” This new model will come with a new-found respect for the large hospitality industry that drives it. Restaurants and hotels are the true industrial backbone, the solid infrastructure, and the real drivers of the new economy. This may actually be the time when we all finally notice and acknowledge how important the work, and the workers, in hospitality are to all of us.